|

The South Carolina Society

of the

Sons of the American Revolution

|

|

The South Carolina Society was organized April 18th, 1889 in a room at the State Capital in Columbia. After the election of officers, the organizing group appointed delegates to the proposed National Convention in New York City to be held later in the month. The National Society was organized April 30th, 1889. Those descendants of our brave ancestors, whose vision and courage gave us our great nation, formed a fraternal, patriotic, and civic organization to perpetuate the basic principles of freedom to honor our founding fathers. The name adopted by the organization was the Sons of the American Revolution.

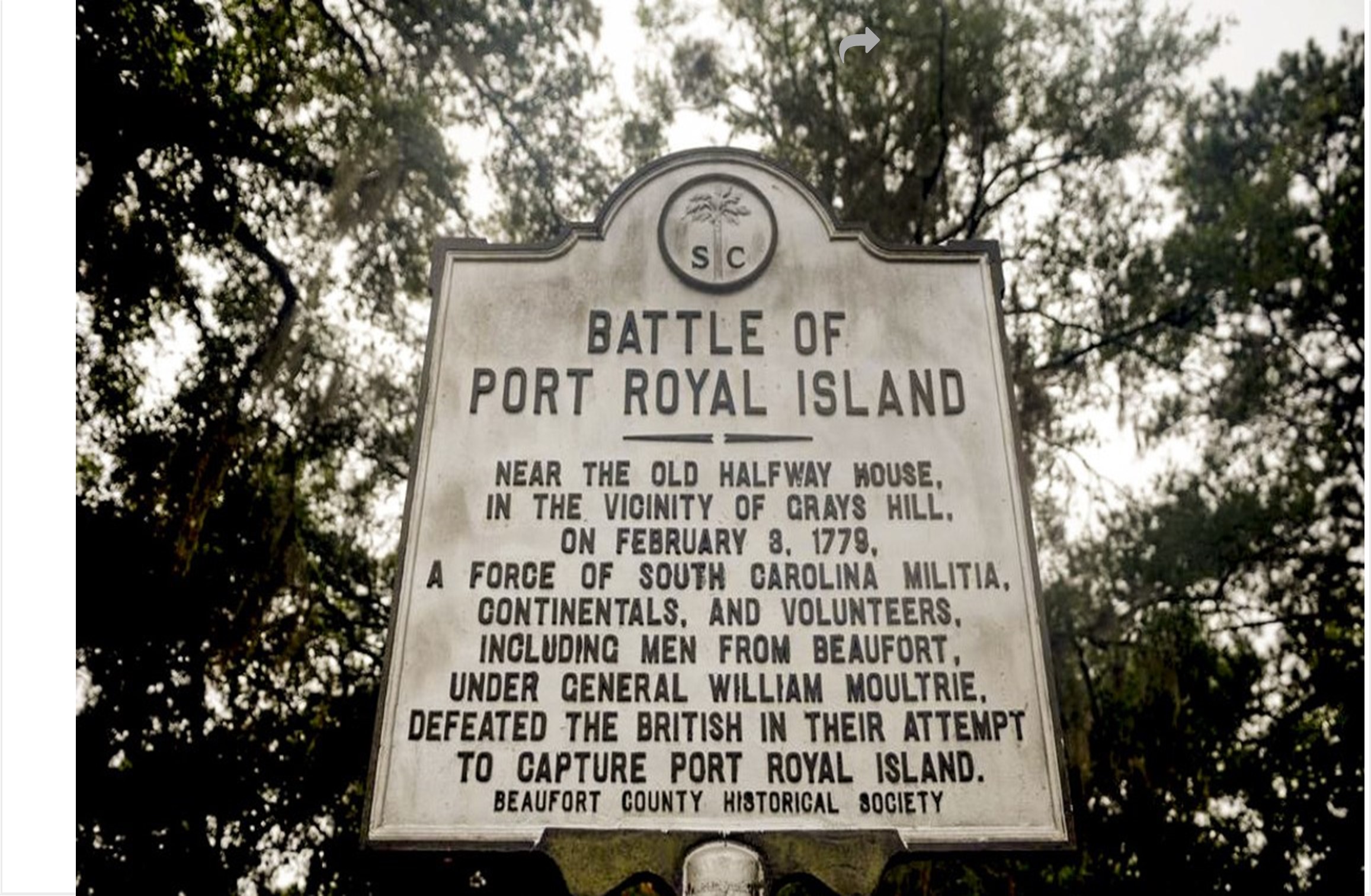

The South Carolina Society began granting charters to chapters in 1923. Currently twenty five chapters, including two who are newly chartered, promote the American spirit through fraternal meetings, commemorative observances of events and battles, educational materials, projects, lectures, tours and publications. South Carolina is rich in historical events of the American Revolution. From the mountains to the coast, South Carolina experienced the most battles and skirmishes of the war. The twenty five chapters of our society sponsor annual anniversary ceremonies of many of the battles and events such as the Battle of Port Royal Island mentioned below.

Relics of the Revolution may be found throughout the state in some federal and state parks, museums, and libraries. Markers are found in our countryside reminding us of the sacrifice of our ancestors. The Society seeks to mark graves of our Revolutionary ancestors.

Since the organization of the South Carolina Society, over 3,000 have filled the membership ranks. As of February, 2024 membership was 813.

The South Carolina Society of the American Revolution joins in effort with the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Children of the American Revolution, Sons of the Revolution and all patriotic and historical groups in keeping alive the ideals of our ancestors who gave us our United States of America.

|

| The Battle of Port Royal Island, SC

aka Battle of Grays Hill

February 3, 1779

|

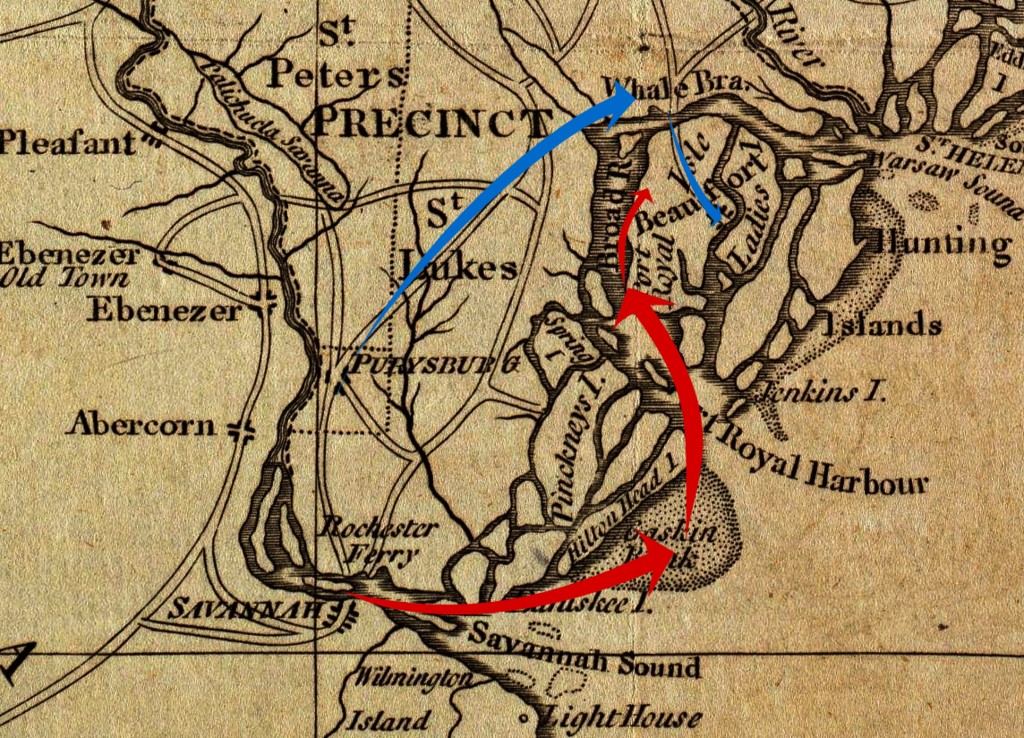

Map of Port Royal Island and Beaufort, SC mid 1700’s. Blue represents Gen. Benjamin Lincoln’s troops while Red represents Maj. Gardiners’s troops.

|

Actions leading up to the Battle

In early 1778 after the French entered into a treaty with the colonies, the British changed its plans of operation turning its attention to the importance of the South. The finest harbor on the Atlantic Ocean, Port Royal, became a source of military interest for future operations. Savannah fell in late Dec 1778 after Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell routed General Robert Howe (NC) and his Americans. By mid- January British General Augustine Prevost (Swiss) joined Col. Campbell in Savannah and started to plan the invasion of South Carolina. At the near same time American Southern forces commander Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (Mass) decided to move his headquarters from Charleston to Purrysburgh, SC just north of Savannah (two miles northwest of today’s Hardeeville) to check Prevost.

British Brig. Gen. Augustine Prevoste |

American Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln

|

Near the end of January, Gen. Prevoste countered by landing 200 handpicked regulars, mostly Tories recruited among the colonies in America, and a howitzer on Port Royal Island near Beaufort. An interesting report was that these soldiers did not wear the traditional “Red Coat” uniforms of the British but one of less conspicuous color. Additionally they were armed much as the typical American back woodsman and not with standard military issue weapons. The use of several transports including the HMS Vigilant, a large de-masted ship unfit for sea duty and HMS Germain, to ferry theses troops through the often shallow waters of Port Royal was reportedly aided by defector Andrew DeVeaux, owner of Laurel Bay Plantation. Prevoste thought that a threat to cut Lincoln’s lightly guarded supply line to Charleston might force him to abandon and retreat from Purrysburgh.

The Battle

On the morning of Feb 2nd Generals William Moultrie and Steven Bull left a small detachment of guards at their mainland camp and moved their army and field pieces by a small ferry over to Port Royal Island taking up the better part of the day to complete this transfer. After sunset he marched the army toward the outskirts of Beaufort, rested his men a few hours and marched into town at sunrise on Feb 3rd.While this was going on, the British forces from Savannah, GA under Major William Gardiner had returned to their ships after burning and plundering neighboring plantations along the Broad River and adjacent areas. However, at daybreak on Feb 3rd three companies of riflemen and some artillery comprising approximately 200 men were again landed on Port Royal Island and proceeded toward Port Royal Ferry.

|

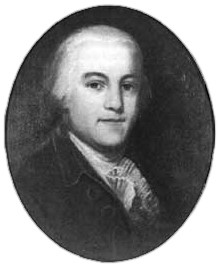

Brig. General Moultrie

|

On that morning Generals Moultrie’s and Bull’s forces in Beaufort were approximately 10 miles from Maj. Gardiner’s forces near Port Royal Ferry. When Gen. Moultrie was advised by scouts that the British had landed once again (probably near Laurel Bay and Clarendon Plantations) and were closing in at five to six miles from Beaufort he hastened to meet the enemy and join battle before they reached Beaufort. Capt. John de Treville and his twenty Continentals of the 4th Regiment of Artillery came out from Beaufort's Fort Lyttleton, the exact spot of the battle has been recently discovered as having been fought near the “Half-way House” which was located between what is known as Grays Hill and the Marine Corps Air Station. Moultrie drew up his troops approximately 200 yards from the enemy placing them on the right and left sides of the causeway with his two field artillery pieces ( 6 pounders) in between with his small piece (2 pounder) on the right in the woods. It has been noted that a reversal of normal fighting positions prevailed as the British were under cover in a swampy area while the Americans were in the open. Moultrie gave the order to fire which Capt. Thomas Heyward, Jr. and Lt. Benjamin Wilkins did promptly with both field pieces, killing two British Officers and Maj. Gardiner’s horse. The enemy's only field piece was struck and dismounted early in the battle. The firing carried on for approximately 30 to 45 minutes when Capt. Heyward advised Moultrie that Lt. Wilkins had been gravely wounded and their ammunition was nearly expended, Moultrie then ordered the Americans to retire slowly. Little did Moultrie know that the British, after suffering losses, had already started their retreat prior to Heyward notifying Moultrie of his limited artillery munitions. This lack of ammunition kept Moultrie from pursuing the British who were retreating to their ships and safe passage back to Savannah. Due to having left the field last, the battle went to the Americans. As the enemy retreated, Capt. John Barnwell of the Beaufort militia and a few men rode around the enemy formation capturing 26 stragglers and nearly panicking Maj. Gardiner’s command as they moved toward their waiting ships. Over 40 British were killed and wounded while the Patriots suffered 8 killed and 22 wounded. After the battle, Gen. Moultrie said that the Americans, untrained militia, had stood well during battle. In addition to Capt. Thomas Heyward, Jr., fellow SC Declaration of Independence signer Capt. Edward Rutledge also participated in the battle.

Capt. Thomas Heyward, Jr.

|

Capt. Edward Rutledge

|

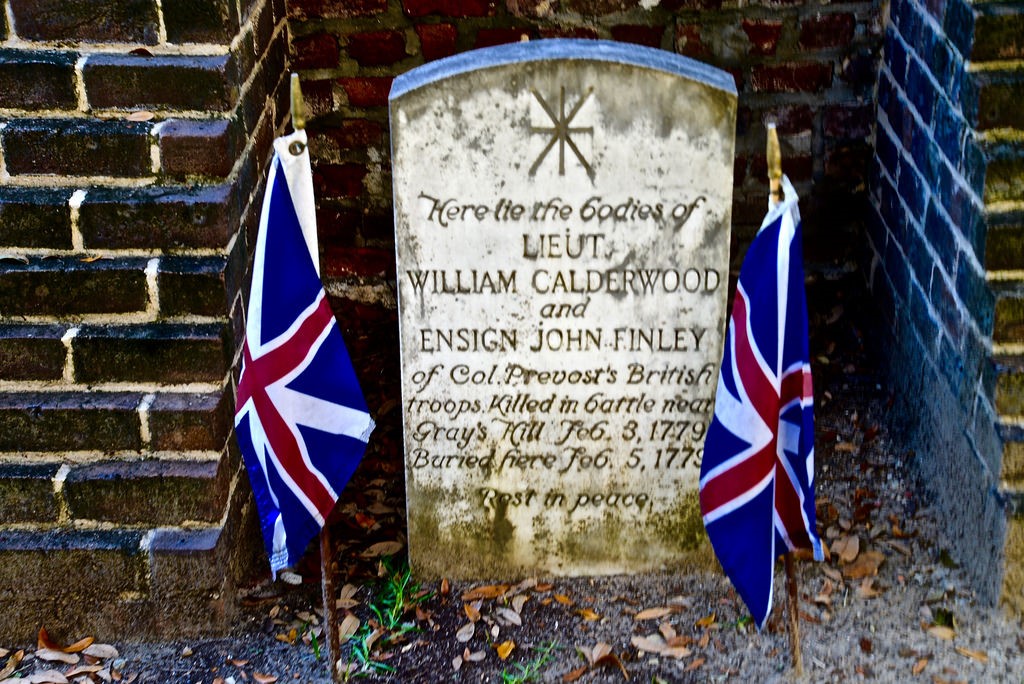

Two days after the battle a prisoner told of the deaths and subsequent hasty burial of British officers Lt. William Calderwood and Ensign John Finley. Several volunteers returned to the battle site to recover the bodies which were easily found buried on top of one another. The bodies were laid in a cart and covered with branches for the trip back to Beaufort. In a published letter dated 1831 or 1832, John Peter Martin wrote to Colin Campbell of Beaufort at Campbell’s request describing this event. The bodies were in full uniform except for hat and shoes, which were missing. Martin went on to say “as a memento I recall cutting a single silver button from each of their coats bearing, if I mistake not, the numbers sixteen and forty-eight, designating the regiment to which they belonged.”

They were once again buried in a common grave, but this time in the yard of St. Helena’s Parish Episcopal Church. “The spot,” he says, “is some twenty yards in front of the steeple or West end of the church and a little to the left.” Mr. Martin went on to “distinctly” recall the closing words of Capt. Barnwell, the officer in charge of the burial. “Soldiers and Fellow Citizens: We have shown our enemies that we not only have the courage to face and beat them on the field, but we have the humanity to give their dead a decent Christian Burial.”

| >

In a contemporary account of this battle of Beaufort, written by a British officer who took part in the fighting, the soldiers from Charleston under Heyward and Rutledge were referred to as the Silk Stocking Company of Charleston, all gentlemen. These troops, however, were probably among the best militia in the American Army as they had been organized and drilled by Gen. Christopher Gadsden (designer of the Gadsden Flag: yellow with coiled rattlesnake and words Don’t Tread on Me) in the early days of the Revolution in this state.

John Peter Miller also wrote a poignant sequel to the story of the Battle of Port Royal Island.

"Among the few killed on our side, I must not omit to name the lamented Lieutenant Wilkins, who fell mortally wounded, while directing one of the field pieces of which he had the command. He expired about twenty-four hours after the action, and was buried in the Beaufort Parish churchyard. Of this amiable man, and brave soldier, I must add, that he was generally admitted to be the best marksman in the battalion, when practicing with round shot at a target. His name was afterwards engraven on the piece at which he fell, which continued a sacred memento to the battalion until among others, it came into the hands of the British at the reduction of Charleston in May 1780.”

Over the years his grave marker was lost and in April of 2010, family descendants were granted approval by the Parish Church of Saint Helena to erect a memorial marker to said Patriot Wilkins, who was written about and whose marker appears in the new “Amazing Grace” publication of the Three Hundred Years of History 1712-2012 of the Parish Church. On June 20, 2014, the Gov. Paul Hamilton Chapter of the South Carolina Society Sons of the American Revolution marked his grave with the SAR Patriot Bronze Marker paying tribute to his patriotic service and the life he sacrificed for the freedom of his country and family.

|

Port Royal Island Battlefield Protected

|

At the close of 2020, Beaufort County succeeded in permanently protecting twelve acres along Highway 21, known as The Port Royal Island Battlefield. This Revolutionary War battlefield contains significant historic value and artifacts and is protected as a critical piece of the county’s rich cultural landscape.

To read the complete article Click on: "Port Royal Island Batlefield Protected" or for more information visit "Beaufort County Rural and Critical Land Preservation Program"

|